The Hiroshima Panels

The Hiroshima Panels (I)-(XIV) are on display permanently at Maruki Gallery.

* The Hiroshima Panels (XV) “Nagasaki” is on display at the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum.

We lost our uncle to the atomic bomb. Two young nieces were killed. Our younger sister suffered burns, and our father died after six months. Many friends and acquaintances perished. Iri left for Hiroshima on the first train from Tokyo, three days after the bomb was dropped. Toshi followed a few days later. Just over two kilometers from the center of the explosion, the family home was still standing.

But the roof and roof tiles and windows were blown away by the blast, along with pans, bowls, and chopsticks from the kitchen. Even so, the burned structure remained, and large numbers of injured people had gathered there and lay on the floor from wall to wall. We carried the injured, cremated the dead, searched for food, and found scorched sheets of tin to patch the roof. With the stench of death and flies and maggots all around us, we wandered about just as those who had experienced the bomb.

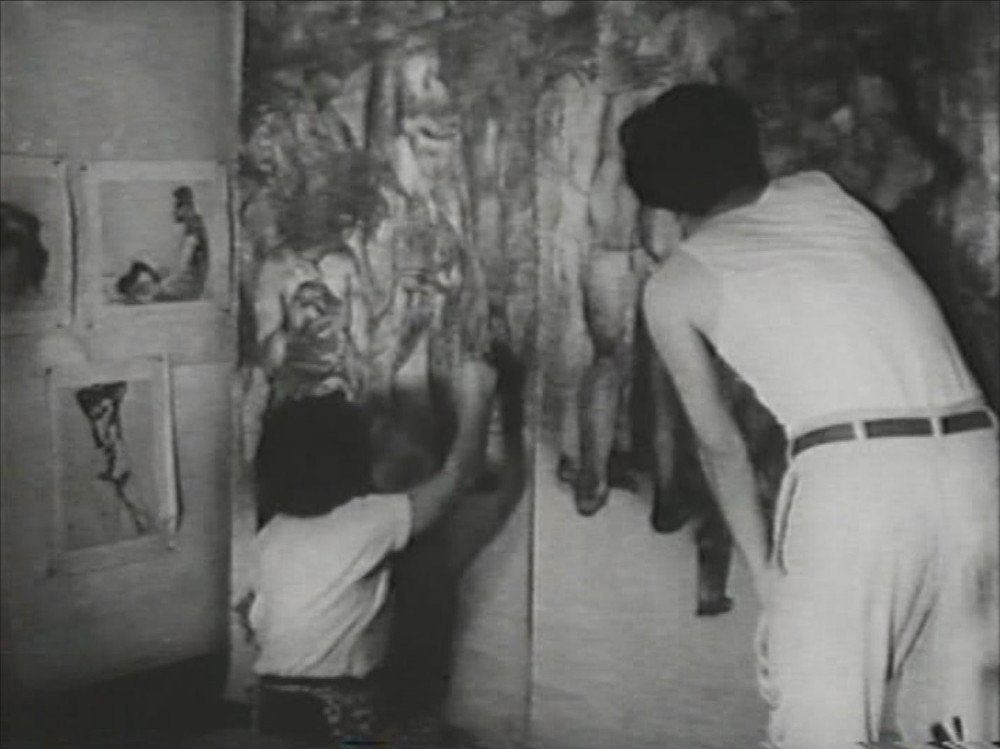

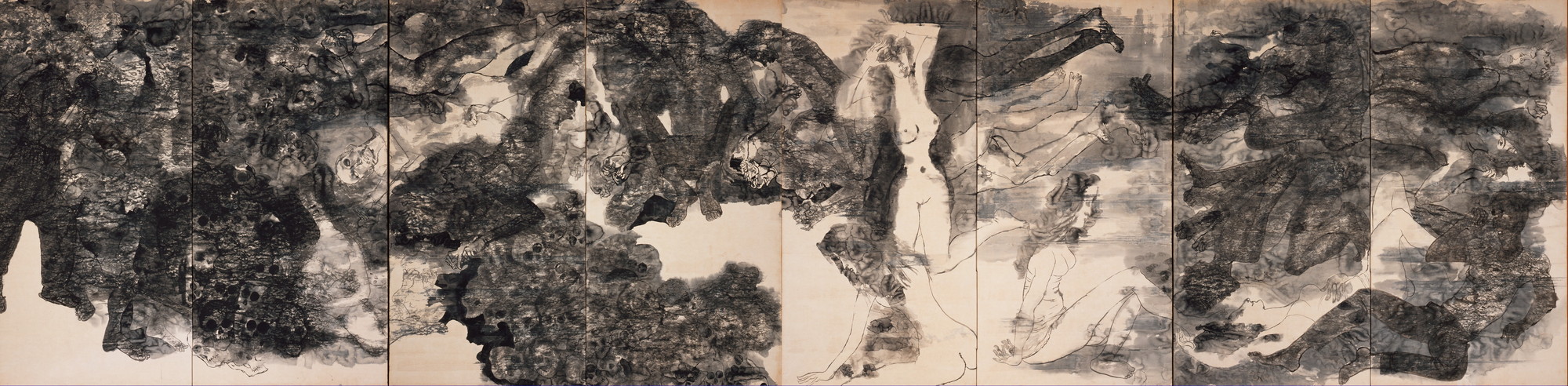

In the beginning of September, we returned Tokyo, and we learned for certain that the war had ended. In Hiroshima, we had lost the strength to think about whether the war had ended or not. Three years passed before we began to paint the Hiroshima Panels. We stripped our clothing to recall images from that time and draw them, and others agreed to pose for us because we were painting the atomic bomb. We began thinking how a 17-year-old girl had a life span of 17 years, how the life of a 3-year-old child had lasted three years.

We painted some nine hundred human figures, including the sketches, for the first painting. We thought we had painted a large number, but as many as 140,000 people died in Hiroshima. As we continued painting, praying for the souls of the dead in the hope that it will never happen again, we realized that even if we painted all our lives, we could never paint them all. One atomic bomb in one instant caused the deaths of more people than we could ever portray. Longlasting radioactivity and radiation sickness are causing people to suffer and die even now. This was not a natural disaster. As we painted, through our paintings, these thoughts ran through our minds.

Maruki Iri

Maruki Toshi

“Pika!” A strong blue-white flash. The explosion, the pressure, the firestorm—never on earth or in heaven had humankind experienced such a blast. Flames burst out in the next instant and leapt skyward. Breaking the stillness over the boundless ruins, the fire roared.

Some lay unconscious, pinned by fallen beams. Others, regaining their senses, tried to free themselves, only to be enveloped by the crimson blaze.

Glass shards pierced bellies, arms were twisted, legs buckled, people fell and were burned alive.

Hugging her child, a woman fought to free herself from beneath a fallen post.

“Hurry! Hurry!” someone shouted. “It’s too late.” “Then hand us the child.” “No, you run. I will die with my child. She would only be left to wander the streets.”

The woman pushed away the helping hands and was consumed by flames.

1950 Sumi ink, pigment, glue, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

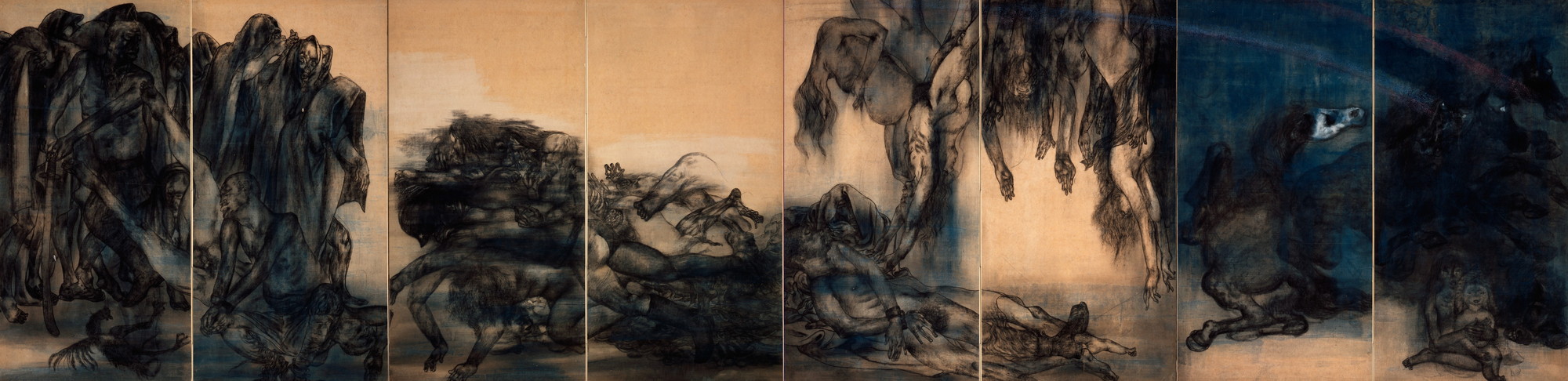

There were mountains of corpses, piled with heads at the center of the mound. They were stacked so their eyes, mouths, and noses could be seen as little as possible.

In one yet uncremated mound, a man’s eyeball moved and stared. Was he still alive? Or had a maggot moved his dead eye?

Water! Water! People wandered about, searching for water. Fleeing the flames, crying for water to wet their dying lips. An injured mother with her child fled to the riverside. She slipped into deep water, scrambled along the shallows. Running as the raging fire engulfed the river, stopping now and then to wet her face, she ran on until finally she came to this spot. She offered her child a breast, only to find it had breathed its last.

The twentieth-century image of madonna and child: an injured mother cradling her dead infant. Is this not an image of despair? Mother and child should be, must be a symbol of hope.

1950 Sumi ink, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

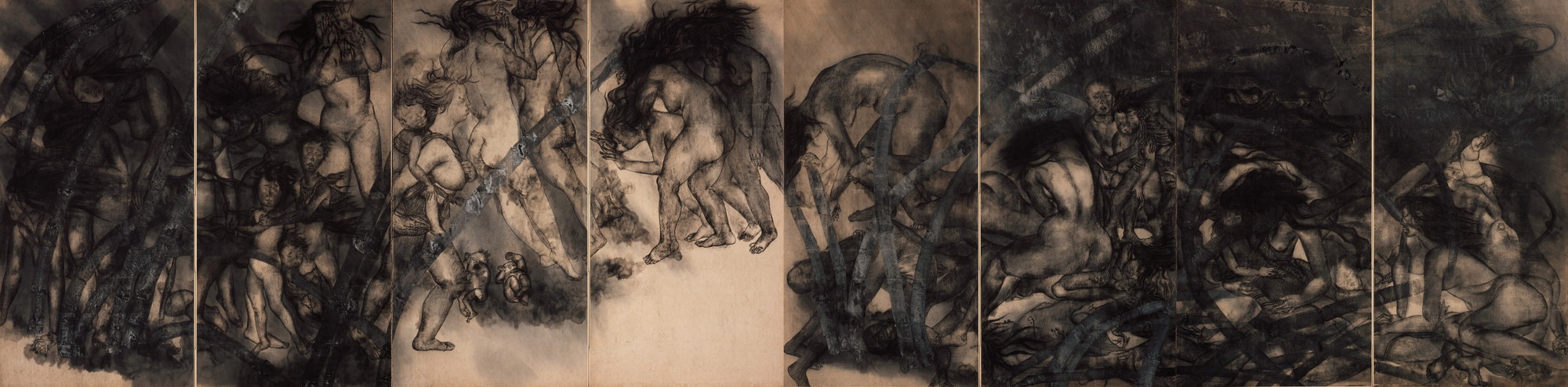

A naked soldier stood with only his boots and sword. Young soldiers with broken arms and crushed legs. The injured ran aimlessly, their ragged skin covered with blankets.

There was no sound, just dead silence. Then a crazed soldier pointed to the sky and shouted over and over, “An airplane! A B-29!” There was not a shadow of an airplane to be seen. Injured horses, frenzied horses ran amuck.

American airmen, who came to bomb Japan, had been seized and placed in a Hiroshima barracks. The atomic bomb killed friend and foe alike. Two soldiers lay crumpled on the road near the dome, their wrists still handcuffed.

The smoke and dust blown high into the air formed a cloud, and soon large raindrops poured down from the otherwise clear sky. A rainbow arched across this blackened dome. The seven-colored rainbow shone with brilliance.

1951 Sumi ink, pigment, glue, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

They lay dead in heaps along the riverbank, their heads pointing toward the water they had been seeking. Having reached the river, the water remained out of reach below the steep bank, and they died with their thirst unquenched.

Schoolchildren had been mobilized to help build firebreaks. Many classes were entirely annihilated.

Two sisters held each other’s transformed figures. Other young girls died without a scratch on their bodies.

When he saw this painting, a carpenter who had been exposed to the bomb told us, “My daughter is the sole survivor of her class. But her fingers were twisted and burned together, her face became fused to her throat, and she cannot walk. Her body has not grown since then, when she was thirteen years old.”

1951 Sumi ink, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

Nothing to eat, no medicine. No shelter from the falling rain. No electricity, no newspapers, no radio, no doctors. Maggots bred on corpses and the wounded, clouds of flies swarmed and buzzed. The smell of corpses hung on the wind.

People were not only injured physically, their spirits were also deeply wounded.

A woman, unmindful of covering her ragged skin, searched for her child. She wandered about for days on end.

Even today, human bones are sometimes unearthed in Hiroshima.

1952 Sumi ink, pigment, glue, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

Many took shelter in a bamboo grove. —It wasn’t an earthquake, but what was it? —Could it have been a cluster of firebombs? —It was a bomb, no, a death ray. —In any case, there was a flash—pika—then a roaring thunder—don. —No. In Hiroshima, we didn’t hear any thunder. It was so large, there was only a flash.

They talked on about that moment. There were many bamboo groves on the outskirts of Hiroshima, and the atomic bomb seared the bamboo on one side. The homeless took shelter in the groves. And one by one they breathed their last.

People called out to us for help, but we lacked the courage to go to them. There was no more room for the injured in our house.

Under Mitaki Bridge, there was a heap of corpses. One person crouching there appeared to be alive, but we could not tell its age or sex. By the morning of August 26, the person’s head fell forward and he or she died. The bomb was dropped on August 6, so this person had endured in silence for twenty days. There was no one to dispose of these corpses, and they were not moved until a typhoon in September washed them out to sea.

1954 Sumi ink, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

The fires burned and burned.

People from the countryside came to search for relatives and carried them out of the city. Many died along the way.

Long lines formed to receive rations. A girl died nearby, still clutching her portion of hardtack.

Glass shards were embedded throughout the bodies of the parents of our sister’s husband. Their ankles swelled as large as their thighs. They had taken refuge in our home, and we decided to take them to their eldest son. We placed them on a cart and pulled it all the way to Kaita, passing through the center of the blast. A gentle rain was falling.

After the bomb, it rained often in Hiroshima. Even though it was August, one cold day followed another.

Someone told us amid sobs, “I left my mother. I cried, ‘Forgive me!’” In the frantic effort to escape, wives and husbands had to abandon each other, parents had to desert their children.

Many days passed before relief was organized.

1954 Sumi ink, pigment, glue, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

The first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima in 1945, followed by a second bomb on Nagasaki.

In 1954, a hydrogen bomb exploded on Bikini atoll. The crew of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, a fishing boat from the port of Yaizu, was showered with the ashes of death. Six months later, Kuboyama Aikichi died. Three times the Japanese have fallen victim to nuclear weapons.

[Afterword, May 1983]

Not only the Japanese, but Micronesians near Bikini atoll were dusted with the deadly fallout from the hydrogen bomb. The entire island was polluted. Those who fled later returned to their native Bikini, only to develop cancer and leukemia from the residual radiation. Many suffer still.

Yaizu and Bikini—a shared fate.

1955 Sumi ink, pigment, glue, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

Stop the atomic bomb! Stop the hydrogen bomb! Stop war!

The appeal of mothers in Tokyo’s Suginami Ward spread throughout Japan. Children, mothers, fathers, elders, and workers of all kinds signed the petition.

For the first time, a voice was given to the people’s muffled cry, and millions signed the petition for peace.

1955 Sumi ink, pigment, glue, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

Parents were forced to abandon children pinned under fallen houses, children abandoned parents, husbands abandoned wives and wives husbands, all in frantic flight from the blaze. This was reality at the time of the atomic bomb.

Still, in the midst of this, many witnessed the miraculous sight of children who survived, held tightly in their dead mothers’ arms.

1959 Sumi ink, pigment, glue, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

On August 6, the seven rivers of Hiroshima fill with floating lanterns, inscribed with the names of fathers, mothers, sisters.

The tide shifts before the lanterns reach the sea, and they are swept back to the city by the swell. Extinguished now, the mass of crumpled lanterns drifts in the dark currents of the river.

On that day in the past, these same rivers flowed dense with corpses.

1968 Sumi ink, pigment, glue, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

Some three hundred thousand Japanese died from the atomic bombs you dropped. But your atomic bombs also killed twenty-three youths from your own country. Americans who had parachuted from B-29s on air raids before the bombing of Hiroshima were held there as prisoners of war. Some said there were also women POWs.

We wondered what they looked like when they died, what clothing, what shoes they wore.

We went to Hiroshima, and we were shocked at what we discovered. Since the American POWs were held in underground shelters near the center of the blast, they probably would have died before long. Or, just maybe, some might have lived. But before their fate could be known, Japanese slaughtered them, we learned.

We trembled as we painted the death of the American prisoners of war.

[Editor’s note]

June 2019: It is now estimated that total deaths from the atomic bombs by the end of 1945 numbered about 140,000 in Hiroshima and about 74,000 in Nagasaki. However, these estimates date from around 1976 or 1977; it was previously thought that more than 200,000 had died in Hiroshima alone. There are still no accurate figures for the number of people who died from the effects of the bombs after 1945. It is now generally believed that 12 American prisoners of war died in Hiroshima, though it was previously thought that the number was 23. It was rumored that some of the POWs were women, but this has not been confirmed. There are numerous eyewitness accounts of a POW who was tied to a post at the eastern end of Aioi Bridge, and of people throwing stones at him.

1971 Sumi ink on paper

180 × 720 cm

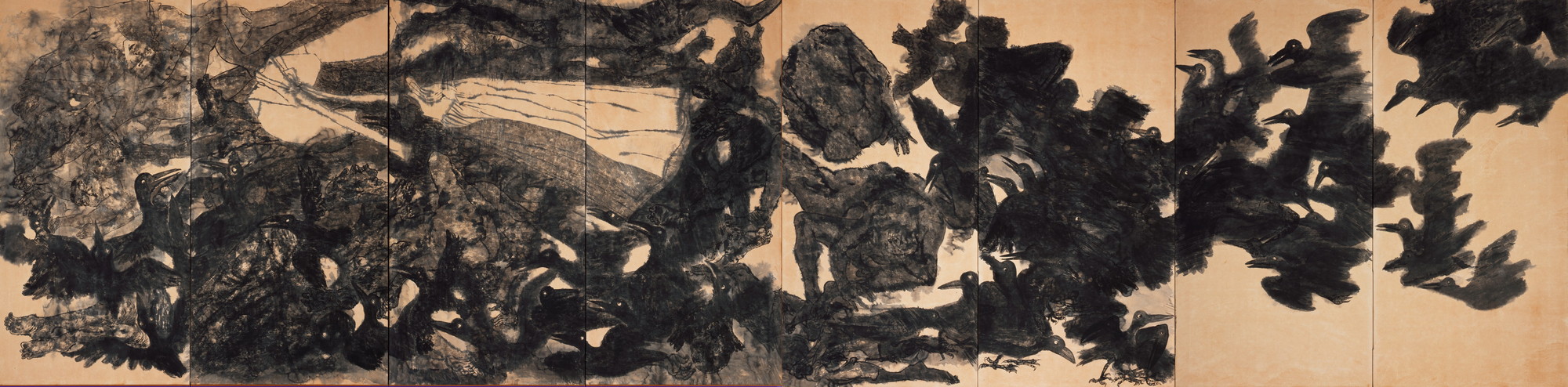

Japanese and Koreans look alike. How could one mercilessly burned face be distinguished from another?

“After the bomb, the last corpses to be disposed of were the Koreans. Many Japanese survived the bomb, but very few Koreans did. There was nothing we could do. Crows came flying, many of them. The crows came and ate the eyeballs of the Korean corpses. They ate the eyeballs.” (From the writings of Ishimure Michiko.)

Koreans were discriminated against, even in death. Japanese discriminated, even against corpses. Both were Asian victims of the bomb.

Beautiful chima and chogori, fly back to Korea, to the sky over the homeland. We humbly offer this painting. We pray.

Some five thousand Koreans died en masse in Nagasaki, where they had been brought as forced labor for the Mitsubishi shipyards. There are similar stories about Koreans in Hiroshima.

In South Korea alone, nearly fifteen thousand hibakusha live today, without official recognition of their status as atomic-bomb survivors.

[Editor’s note]

June 2019: The city of Nagasaki estimates that between 1,400 and 2,000 Koreans were exposed to the bomb in Nagasaki. The total number of hibakusha residing outside of Japan is not known. According to the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, approximately 3,200 people outside of Japan had been issued atomic bomb survivor’s certificates as of 2018.

1972 Sumi ink on paper

180 × 720 cm

The target city of Kokura was covered by thick clouds, and the two B-29s flew on to the alternate target, the port of Nagasaki. Here too the visibility was poor, so the atomic bomb was dropped on the Mitsubishi steelworks on the edge of the city.

The bomb exploded directly above the Catholic cathedral in Urakami, killing the priests and those who had gathered there to worship. The dead were scattered in endless concentric circles, with the cathedral at the center.

The Nagasaki bomb was made from plutonium and was more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb. One more atomic bomb. Nagasaki was devastated. One hundred forty thousand people died.

1982 Sumi ink, pigment, glue, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm

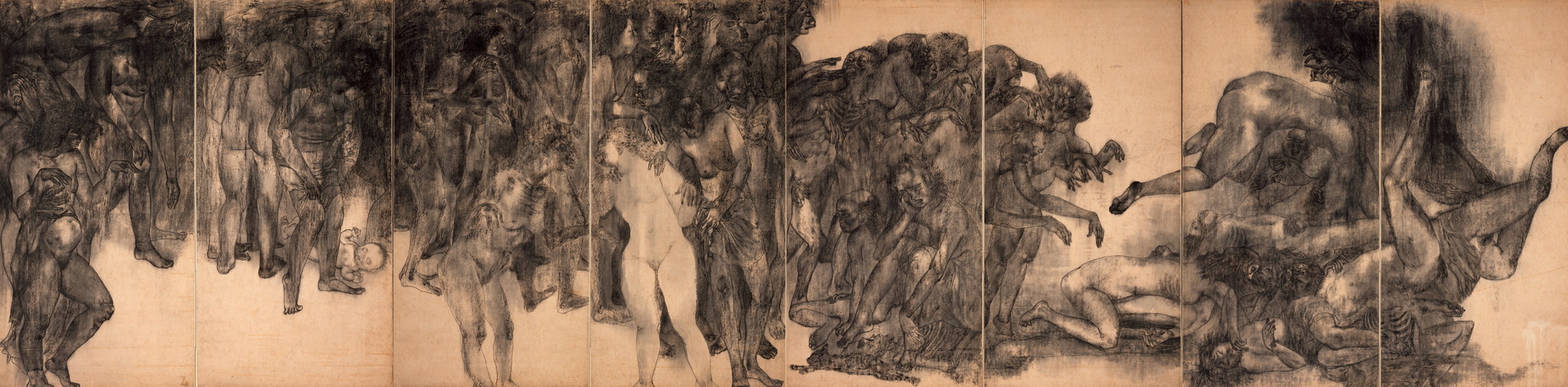

It was a procession of ghosts.

Clothes burned in an instant. Hands, faces, breasts swelled; purple blisters soon burst and skin hung like rags.

A procession of ghosts, with their hands held before them. Dragging their torn skin, they fell exhausted, piling onto one another, groaning, and dying.

At the center of the blast, the temperature reached six thousand degrees. A human shadow was etched on stone steps. Did that person’s body vaporize? Was it blown away? No one remains to tell us what it was like near the hypocenter.

There was no way to distinguish one charred, blistered face from another. Voices became parched and hoarse. Friends would say their names, but still not recognize each other.

One lone baby slept innocently, with beautiful skin. Perhaps it survived, sheltered by its mother’s breast. We hope that at least this one child will awaken to live on.

1950 Sumi ink, charcoal or conté on paper

180 × 720 cm