Collaborative Works

After their completion, the first three ‘Hiroshima Panels’ were exhibited in various places in and outside of Japan.

The panels would often be delivered into the hands of the exhibiter, but sometimes the Marukis would travel along with the panels.

They have traveled far and wide, met many people, and heard many stories.

That is how there came to be a total of fifteen ‘Hiroshima Panels’. But there’s more.

For example, the Marukis learned about Minamata Disease upon visiting France.

They knew it was a disease caused by pollution, but they did not know the details.

Afterward, the Marukis visited Minamata to meet with local people, survivors and their families, and they created the ‘Minamata’ panel.

For example, the Marukis heard about the Nanking Massacre upon visiting the USA.

The host of ‘The Hiroshima Panel’ exhibition in the USA asked them,

“If a Chinese artist said, ‘I want to create artwork depicting the Nanking Massacre,’ what would you say? I believe it would be exactly what we are trying to do with ‘The Hiroshima Panel’ exhibition.”

The Marukis decided that since no Chinese artist had stepped forward, they would depict the massacre, and they created the ‘Rape of Nanking’ panel.

They also visited Auschwitz.

When Narita Airport was built, they met with the farmers who lived on that land.

They stood in solidarity with people opposing nuclear power plants that could cause the same harm as atomic bombs.

The Maruki Gallery is home not only to ‘The Hiroshima Panels’, but to many collaborative works of art.

These works depict the harm afflicted upon people, caused by people. Just like war, these events must never be repeated again.

A flight to Warsaw, a plane change and on to Krakow.

Overnight, then westward by taxi.

Rolling hills of light green, grassy plains, wheat fields.

Close now to the Czechoslovakian border.

The land is low here.

“ ‘Auschwitz’ is the German name. Please use the Polish ‘Oswiecim’, ”

said a gentle young man.

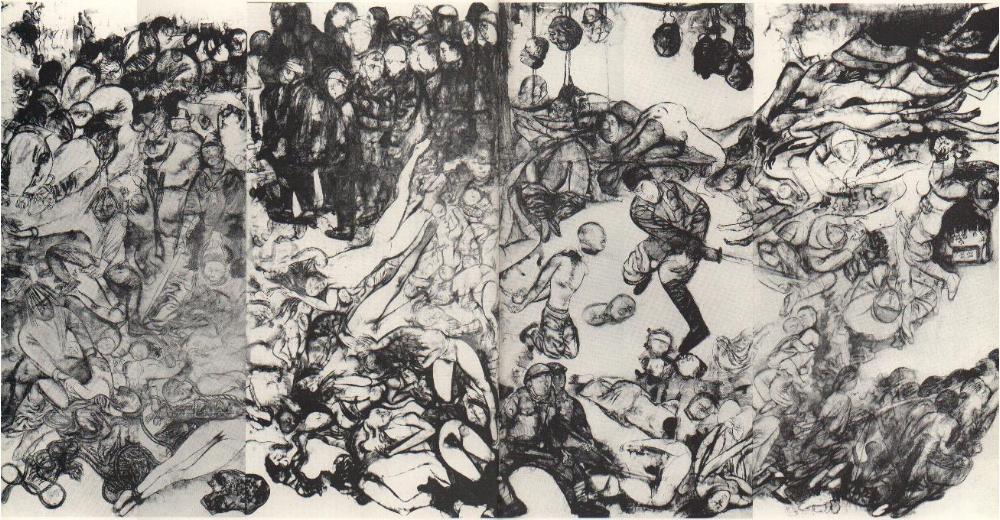

On Hitler’s orders, Jewish people from 29 countries were uprooted and taken to camps.

Four million people were murdered at Auschwitz alone.

In the beginning, it was done by machine-gun.

Then, for greater numbers at one time, poison gas.

Here a mountain of frames from which the glass lenses had been taken;

there a mountain of human hair

— blonde hair, brown hair, white hair —

in this mass a child’s hair tied with a red ribbon.

Rugs woven from human hair were on display;

the Hitler government would distribute them to German households.

Plaster casts, canes, shoes — a mountain of each.

Each of the people from whom these had been taken had been sent to their deaths in the gas chambers.

It began to rain.

Soon the ground was wet and puddles began to form.

In the twilight, the gallows and scaffolds were enfolded in the encroaching darkness.

“Minamata is not only a thing of Japan in far-off Asia.

Bretagne has the problem. The Basque district, too”

“Tell us more about Minamata,”

said many people we met in France.

Upon returning to Japan, we soon left for Minamata.

As we stepped into the household of one family, the young daughter sudently went into a convulsion.

“Quick, bring a towel!” shouted the mother.

The strength of the attack would rub the child’s knees together uncontrollably, and they would bleed.

The pretty girl’s black hair was glitening with perspiration,

her backarched tight as a bow.

Later, breathing heavily, she looked at her visitors.

Our feet rooted, we couldn’t say a word, couldn’t draw a thing,

and just tried to silently apologize for having intruded.

Minamata Chisso Factory seeped waste brimming with mercury into the calm waters of the bay.

The abundant fish eat the mercury; cats eat the fish, people eat the fish.

Fish, birds, cats, people — all the living things of Minamata suffering and dying.

The mother in this family had a light case of mercury poisoning and,

as mercury crosses the placenta with ease, her baby daughter was born with a very heavy case.

She was born a Minamata Mercury Poisoning patient.

The goverenment officially recognizes only 2,200 patients,

while 18,000 more are trying to achieve this status.

Their suffering continues.

Shiranui Sea, with the sun reflecting on it, was glitteringly alive and gorgeous.

But in and around the bay, in the islands, towns, and villages,

many people are dying, and more than 100,000 people are affected in some way.

These tragedies are not told to us by the beautiful clear waters and light island shadows.

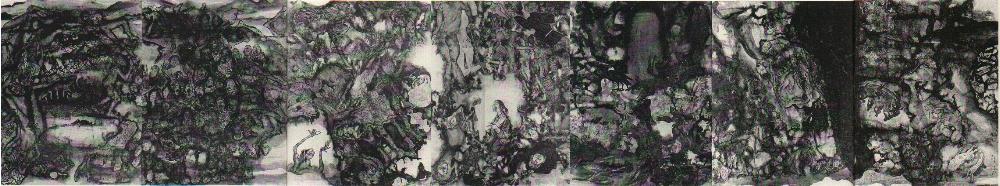

Putting a tarp down in the yard, spreading out ten blankets on top of that,

then laying down the four large sheets of Japanese paper

— we have a paper canvas of four meters by eight meters.

Sitting down on the paper and beginning to paint.

Under my knees, coral reef stone

— the sharp edges of the limestone hurts.

Cleaning the area first, I had stooped to pick up an old cartridge.

We are in Shuri, a site of fierce fighting.

Could the thoughts which people thought as they lost their lives on this spot have seeped down into this stone and now be coming back into my body?

I have come from far away; it is only here that I can paint it.

The sky, the wind, the water, the soil, the grasses, the birds

— silent, they move our brushes for us.

I so want to paint the deep deep blue of the sea.

And the emerald green of the reef dyed orange as the young girls sank below its waters.

Crimson, vermillion — is it the flowing blood of the youth?

Is it the flames that chased those who ran desperately?

Either, both, are true.

From the sky, the camera crew filmed our painting from all sides.

A large empty space on a slant we hadn’t touched was impressive

— more painting is not always better.

We must keep this space alive

— I struggled to control my impatient hand and left it as it was.

For a while.

As the painting went with the currents, it became at last impossible.

Upsidedown, falling.

A young woman under suspicion for spyng, pushed to madness under torture.

Her life taken by the bamboo spear of the Japanese soldier

Painting her on that empty space

— the horror of it haunted me.

One standing, one with head bowed, one sitting.

The tree children are alive.

And with that, our canvas was complete.

In 1970, we took The Hiroshima Panels to the United States.

At the California Institute of Technology near Los Angeles, a university professor asked us,

“If a Chinese artist painted the brutal massacre of Chinese in Nanking by the Japanese Occupation Army, and brought that painting to Japan, what would you do?

It’s the same thing.

Here, Japanese artists have painted the genocide they suffered at the hands of Americans, and have brought it to America.

We are helipng to put on the exhibition.”

At that time, the bombing of Vietnam was going on night and day

— there was the Song My (My Lai) Massacre.

To be exhibiting anti-war paintings in America at that time was very difficult.

We never dreamed that we would hear about Nanking in the United States.

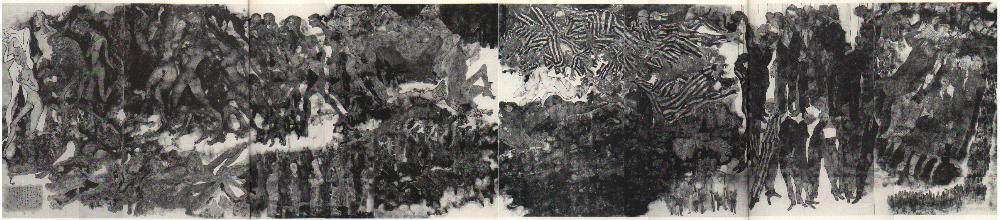

Fifty thousand Chinese prisoners and 350,000 civilians.

In 1937, the number of people slaughtered in Nanking alone by the Japanese Occupation Army equals the number of victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki put together.

Pillage and plunder. Arson. Rape. In the end, vicious murder of them all and dumping of the bodies.

Every imaginable act of violence was committed in Nanking.